Seven years after the height of the financial crisis, Europe’s large banks still behave as if they are in the thick of the storm. Plans for radical restructurings are shelved before they are even implemented, often accompanied by management defenestrations—Barclays is one of four big European banks with new leaders. And they have dithered on the most basic questions, for example on how much capital they need or whether to scale back misfiring investment-banking arms.

YOU wait ages for a European bank to send a clear signal on its future strategy and then it gives two in as many days—saying seemingly opposite things. On October 11th the chairman of Barclays hinted its investment-banking unit might be flogged to a rival for want of scale. Investors intrigued by the prospect of a simpler Barclays focused on dull-but-reliable retail banking had but a few hours to ponder the prospect. By the next day reports emerged that the same chairman had plumped for a former J.P. Morgan investment banker, Jes Staley, to be the bank’s next boss.

European indecisiveness stands in sharp contrast to America’s large banks, which restructured more quickly. Returns are below pre-crisis levels, but their balance-sheets are stronger and management teams bedded in. European banks are still weighed down by non-core units and dud loans; America’s banks have moved on.

Investors have noticed. Most big European banks, including Deutsche Bank and HSBC, trade at a discount to tangible book value: in theory, they would be better off wound up and money returned to shareholders. Bar Citi, America’s largest banks trade at a premium to book value. Shareholder returns for big American and European banks used to track each other; now a chasm has opened up (see chart 1).

In investment banking, Wall Street is relentlessly gaining market share at Europeans’ expense (see chart 2). The business of helping companies raise money on capital markets, trading bonds and generally shifting money around is one that European banks are not keen to give up. But fund-raising clients are deserting the likes of Barclays and Credit Suisse for Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan.

Many factors help explain the disarray of European banks. Profits across all their lines of business have been hit by years of anaemic economic growth; America’s banks have been lending in a more buoyant environment. Interest rates in the euro zone are set to stay lower for longer, making it harder to generate decent net interest margins from lending. Europe’s banking market is fragmented and includes politically controlled lenders, such as Landesbanken in Germany, which sap profits for everyone.

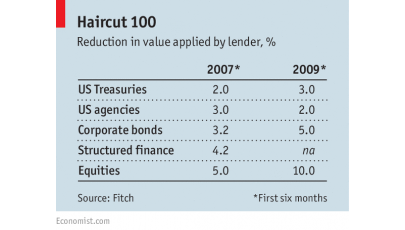

European bank bosses also blame changing regulations for their vacillating strategies. They have had a tougher job adapting to new global rules, which have moved them towards an American model. The introduction of a leverage ratio, which limits the amount banks can borrow in order to make loans, is a transatlantic import. It punishes big banks holding relatively safe assets such as mortgages or government bonds—the essence of European banking. By contrast, American banks act as conduits to capital markets and hold relatively few mortgages on their balance-sheets, thanks partly to government agencies like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Some of the finer print of regulation in Europe has indeed been a long time coming. A new euro-zone banking regulator—a direct consequence of the euro crisis—is only now getting into its stride, nearly a year after it was created. Swiss rules on leverage and British ones on “ringfencing” retail arms, both out this week, have taken ages to emerge.

But Europe’s bankers have also been in denial, confident their political masters would sooner row back on regulation than force them to retrench. Having dithered, they now have to make up ground, most obviously by further slimming down their investment banks. These guzzle capital, and have a knack for attracting multi-billion dollar fines to boot. UBS, a Swiss outfit that throttled its investment bank, is a darling among both regulators and investors.

Rivals unready to go down the same road—not every bank has a lucrative wealth-management franchise like UBS’s to fall back on, after all—stress that investment banks are needed to help firms and governments raise capital. Policymakers want to lean less on banks and more on capital markets. But at current rates, bankers warn, only Wall Street titans will be able to help Europe’s companies find investors or advise them on mergers. Frédéric Oudéa, the boss of Société Générale, a French bank, argued in a Financial Times article this week that having a Europe-based investment bank was a matter of “economic sovereignty”.

That is obviously self-serving. The prosaic truth is that American investment bankers are more efficient. A large part of that is home-turf advantage: half of all global investment-banking revenues are generated in America. Size also matters in banking: market-share gains are going to the bigger firms (see chart 3). Europe’s investment banks tend to be smaller.

But American investment banks also have lower costs, having trimmed staff sooner. Around 70% of European investment banks’ income is soaked up by staff costs, about 15 percentage points higher than in America. That, at least, is starting to be addressed. Deutsche Bank’s new boss, John Cryan, has a reputation as a ruthless cost-slasher and is expected to announce massive job cuts soon.

European banks also look more likely to catch up on capital, where they have been deficient compared with their American rivals. Tidjane Thiam, the new boss of Credit Suisse, is expected to raise billions from shareholders. Deutsche Bank is shedding assets, notably its stake in Postbank, an underperforming German retail lender. It has also warned it may forgo a dividend this year for the first time in decades. French banks lag in this regard.

“In any other industry with excess capacity, you’d have consolidation,” says Huw van Steenis, an analyst at Morgan Stanley. Merging two big beasts, or at least fusing their investment banks, would be a way to cut costs. The euro zone’s new regulatory bodies are not opposed: cross-border mergers would be a show of European financial-market integration. But post-crisis rules designed to rein in “too big to fail” banks mean that larger firms attract even higher capital ratios, crimping returns.

As for clients, the need for a European banking champion is hard to see. Excess banking capacity, if anything, serves European businesses well: they pay much less in fees than their American peers for things like listing shares on a stockmarket. Few seem to mind tapping a Goldman Sachs or Merrill Lynch for operations that require global reach. That may annoy European bankers, but is hardly a reason to mollycoddle them. If their investment banks cannot pay their way under the current rules, it is the banks that must change, not the regulations.